Operation Gutt: A gamble that paid off

To mark the 80th anniversary of Operation Gutt, this article looks back at a little-known event that had a major impact on the Belgian economy.

Occupied Belgium

After the outbreak of World War Two, Belgium was invaded by Germany in May 1940 and surrendered shortly thereafter. While the government went into exile in a sign of resistance, the country found itself in the clutches of the Third Reich.

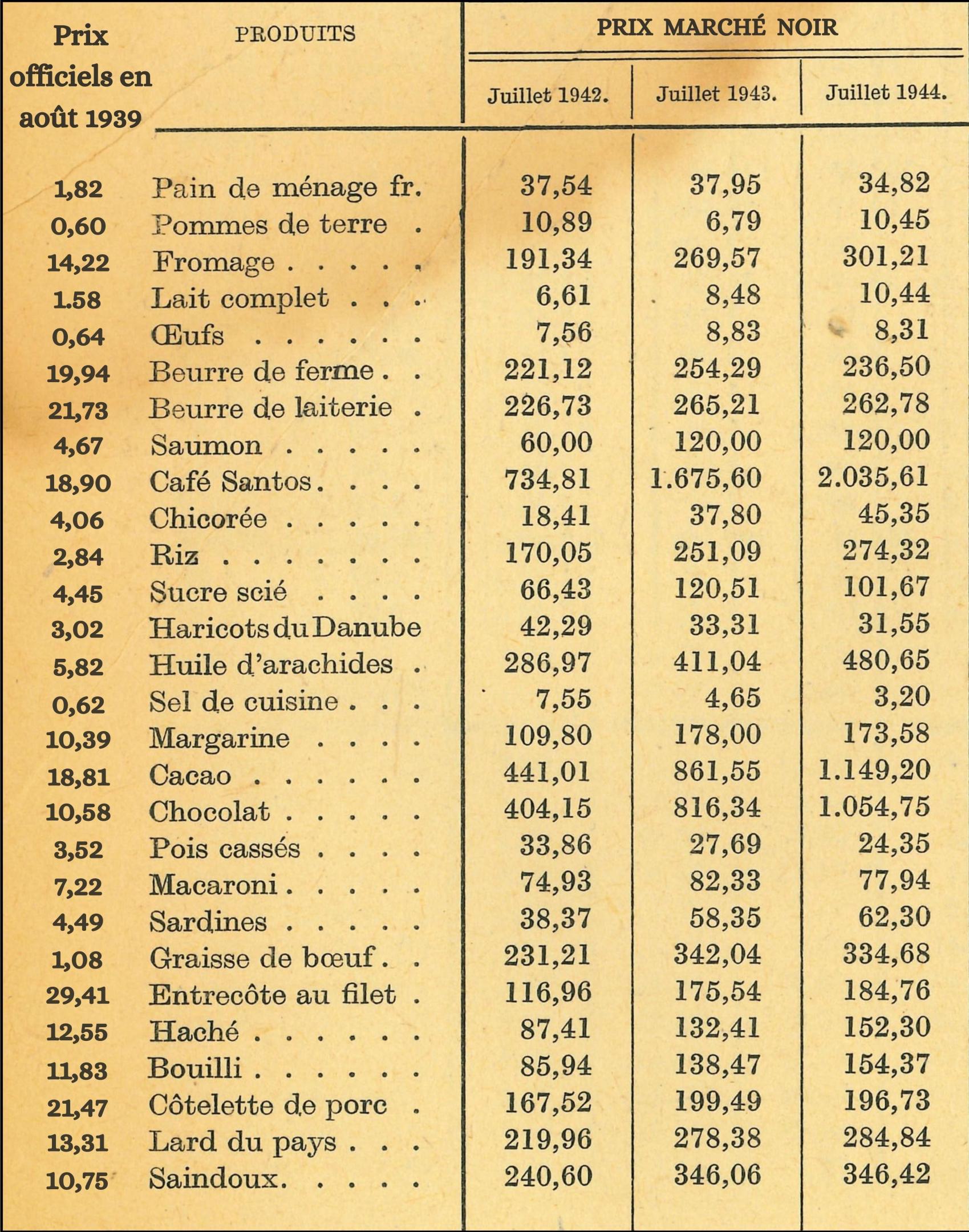

The wave of inflation that had affected a large part of Europe, including Belgium, after the Great War was still fresh in people’s minds, so the government in exile soon began preparing for what would happen after the occupation. During the war, the Nazis undermined the Belgian economy by issuing large quantities of banknotes. Over the four years of the occupation, the money supply tripled. At the same time, the war economy rendered essential goods increasingly scarce and, as a result, more and more expensive. Belgium was plagued by rising inflation throughout the war, which wreaked havoc on its citizens’ purchasing power. By the end of the war, one kilogram of coffee could fetch over 2 000 Belgian francs (BEF) on the black market, whereas in 1939 it cost just under BEF 20. The government in exile therefore saw inflation as seemingly unstoppable and worked hard to find a solution that would avert monetary chaos following the liberation of Belgium.

Inflation 1939-1944 (prices in Belgian francs). Extract from Baudhuin F. (1945), L'économie

belge sous l'occupation 1940-1944, Brussels, Belgium, Etablissement Emile Bruylant.

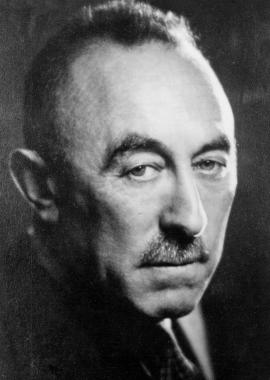

The man behind the solution was Camille Gutt, who served as Finance Minister as early as 1934. An esteemed economist, he devised, along with Adolphe Baudewyns, a director of the National Bank of Belgium, a plan to stabilise the Belgian economy. It was a major monetary, fiscal, social and industrial reform, comprising many different measures, and won the almost unanimous support of monetary and financial experts in occupied Belgium. The plan would go down in history as “Operation Gutt”.

Portrait of Camille Gutt, born Guttenstein, (1884-1971).

Minister of Finance for Belgium (1934-1935 and 1939-1945).

Operation Gutt

Why was it done?

Operation Gutt was in fact only one part of the major reform conceived for the country, yet it is that which lives on in memory. Two technical and social reasons prompted this famous “operation”: first, the government wanted to prevent post-war inflation and gradually eliminate the inflation that was already present in order to bring purchasing power back in line with wages. Second, it aimed to track down illegal German assets and expose the ill-gotten gains of Belgian war profiteers.

To achieve these goals, Operation Gutt removed all banknotes starting from 100 Belgian francs from circulation and replaced them with a new series of notes. This manoeuvre enabled the NBB to gain a better overview of the country’s money supply.

How was it done?

For the operation to succeed, it was important to act quickly to catch unawares those who had collaborated and gotten rich during the war, often by profiting from the misery of others. Thus began a race against the clock: new banknotes were printed in London starting in March 1944, while the war was still raging. The Normandy landings took place on 6 June and the liberation of Belgium was proclaimed on 2 September. On Friday, 6 October, Minister of Finance Camille Gutt announced his plan to the Belgian population during a radio broadcast. In this way, the public learned that from Monday, 9 October, to Friday, 13 October, they were requested to exchange their banknotes at the National Bank of Belgium in Brussels or one of its branches across the country. Belgians therefore had no more than five days to exchange the banknotes in their possession, after which time the latter would simply cease to be legal tender in the country; any banknotes not turned in would be worthless. The operation concerned all denominations from BEF 100 onwards. Banknotes of BEF 50 and below were allowed to remain in circulation, as were coins.

However, there was a limit on how much could be exchanged. A maximum of BEF 2 000 per member of a household (collected by the head of the household) was set. This meant, for example, that a single person living alone exchanging BEF 50 000 at an NBB branch would leave with only BEF 2 000. Did this mean that the government confiscated the remaining BEF 48 000? Not exactly: the remainder was deposited in a special bank account. Although these funds could not be withdrawn immediately, the government promised that they would be used for other purposes, such as paying taxes and other duties, but only after a thorough check! In the meantime, the account was frozen. The government, on a crusade against collaborators, reviewed each potentially suspect account on a case-by-case basis.

In the years following Operation Gutt, the government pursued a strict policy against profits deemed to be ill-gotten war gains. Forty percent of the assets frozen in these accounts were gradually released by the government as the economy recovered. As for the remaining 60%, since people had continued to live, work and spend during the war years, the term “war profits” covered almost all of these amounts, which were taxed at a rate of 70% to 95%. However, a more stringent tax of 100%, known as a confiscatory tax, was levied on revenue from services provided directly to the enemy.

Bank account holders, of which there were relatively few at the time, also saw their assets frozen. They were given two choices: they could receive back either 10% of the amount held in their accounts on 8 October 1944, the day before the launch of Operation Gutt, or the entire balance of the account on 9 May 1940, the day before the German declaration of war on Belgium.

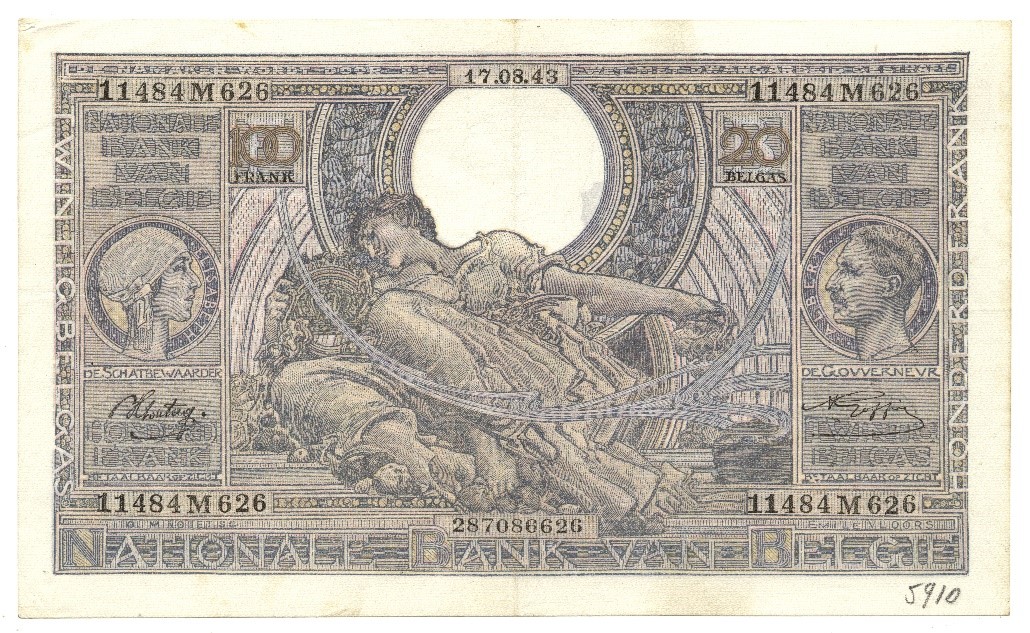

100 banknote from the London series, collection of the Museum of the National Bank of Belgium.

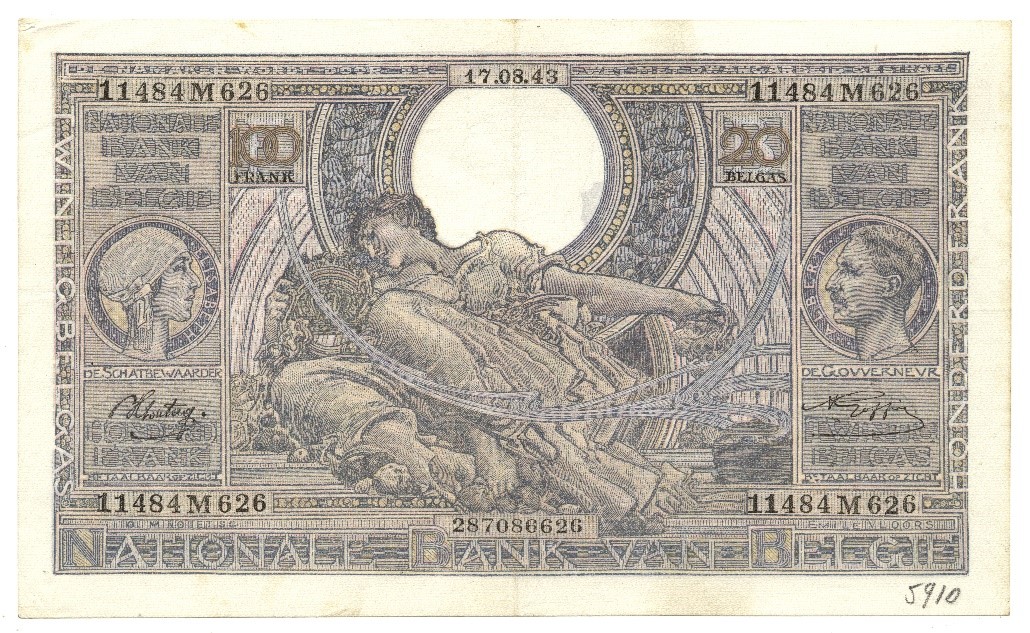

Postcard, collection of the Museum. The central motif has been replaced by a caricature of Camile Gutt.

Was it a good idea?

Operation Gutt took place between 9 and 13 October 1944 and yielded a clear result: the money supply was reduced by two-thirds. Consequently, Belgium emerged quickly from the inflation that arose in the aftermath of the Second World War. Abroad, this prodigious recovery was known as the “Belgian Economic Miracle”, with the country one of only a few directly affected by the war to return, by 1947-1948, to a level of economic activity comparable to that of 1938.

But success was not guaranteed. At the time of this drastic measure, public opinion was not at all favourable, and the Belgian population was even shocked by it. Camille Gutt was seen as an unscrupulous politician, representing a government that would stoop to stealing from its own citizens! He was criticised and caricatured, as can be seen on this postcard depicting a BEF 100 note from the London series. Many citizens did not trust the new “Gutt francs” and some even refused to exchange their banknotes. It is estimated that 4% of the total amount in circulation was never handed in. In fact, even today, it’s possible to find notes stuffed away in suitcases or stashed in other hiding places, by people who hoped to be able to reuse them one day. It’s still possible to exchange Belgian franc banknotes (for euros) at the National Bank of Belgium, but only those with a denomination of BEF 100 or more issued after 1944!

Despite his low popularity among Belgians, Camille Gutt gained international fame and was named the first managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), created following the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. Several countries adopted their own version the now famous Operation Gutt, including the Netherlands, Denmark and Czechoslovakia. France, however, did not and paid the consequences of post-World War II inflation well into the 1960s.

A cache of 22 pre-WWII banknotes, consisting of BEF 100, 1 000, and 5 000 notes. The notes were wrapped in cotton thread and placed inside two bottles. The bottles were buried under the floor of a farmhouse in Laarne and found in 1996. In total, the find amounted to BEF 8 400.

Operation Gutt in our collection

BEF 100 banknote from the London series.

The banknote was designed by Antwerp painter Emile Vloors. The central motif is framed by profile portraits of King Albert I and Queen Elisabeth, facing one another. These are surrounded by the name of the issuer (the NBB), the signatures of the NBB’s treasurer and governor, the denomination, and the words “payable on demand”. The royal portraits are separated by an image of a reclining woman, symbolising Belgium. In her hands, she holds a crown edged with flowers and a garland of fruit, symbols for royalty and abundance. The background consists of a circle bordered by ivy with a portrait of King Leopold I as a watermark.

Postcard, caricature of Camile Gutt.

The central motif has been replaced by a caricature of Camile Gutt. His head rests on a bag of banknotes instead of the royal crown; at his feet is a briefcase; the fruit he holds in his hands, or which surrounds him, is much less abundant than on the original note and has price tags attached to it. The royal portraits have been replaced by the words “Gutt”; in the top right-hand corner the text “do not exceed the indicated dose” refers to the exchange limit of BEF 2000 per household member. In the bottom left corner, the date of 9 October 1944 is that on which Operation Gutt began. Lastly, the name of the issuer – the “Banque nationale de Belgique” – has been altered to read “Banque du compte de Gutt”.

Bibliography

-

National Bank of Belgium. Exchanging Belgian banknotes, available at https://www.nbb.be/en/notes-and-coins/exchanging-banknotes-and-coins/exchanging-belgian-banknotes (accessed on 25 June 2024).

-

BAUDHUIN F. (1945), L'économie belge sous l'occupation 1940-1944, Brussels, Belgium, Etablissement Emile Bruylant.

-

BUYST E. et al. (2005), La banque nationale de Belgique du Franc Belge à l'euro, un siècle et demi d'histoire, Brussels, Belgium, National Bank of Belgium and Les Editions Racine.

-

CASSIERS I. and LEDENT P. (2005), La Banque nationale de Belgique 1939-1971, Politique Monétaire et croissance économique en Belgique à l'ère de Bretton Woods (1944-1971), vol. 4, Brussels, Belgium, National Bank of Belgium.

-

CHÉLINI M-P. (1998), Inflation, État et opinion en France de 1944 à 1952, Vincennes, France, Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France.

-

CROMBOIS J-F. (2001), “Camille Gutt” in Nouvelle Biographie nationale, Brussels, Belgium, Académie royale de Belgique, vol. 6, 228-232.

-

MAES I. (2010), A century of macroeconomic and monetary thought at the National Bank of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium, National Bank of Belgium.

-

TE BOEKHORST B., DANNEEL M. and RANDAXHE Y. (2001), Adieu franc, la Belgique et sa monnaie, une belle histoire, Tielt, Belgium, National Bank of Belgium and Lannoo.

-

VAN DER WEE H. and VERBREYT M. (2005), Oorlog en monetaire politiek: de Nationale Bank van België, de Emissiebank te Brussel en de Belgische regering, 1939-1945, vol. 1, Brussels, Belgium, National Bank of Belgium.

-

VANDEPUTTE R. (1985), Economische geschiedenis van België 1944-1984, Tielt, Belgium, Lannoo.